To speak of certain holy individuals whom we collectively call “victim souls” takes us into territory that many Christians often fail to understand: the redemptive power of human suffering.

A victim soul is an individual who has been chosen by God to undergo physical, and sometimes spiritual, suffering beyond that of normal human experience. The victim soul willingly accepts this unique and difficult mission of offering up his or her pains for the salvation of others.

Although Jesus Christ accomplished our redemption once and for all by suffering torture and crucifixion for our sins, Scripture also affirms the value of human suffering. Christ points to this value himself when He says, “Whoever wishes to come after me must deny himself, take up his cross, and follow me” (Mk 8:34).

Perhaps more pointedly, St. Paul writes that we are “heirs of God and joint heirs with Christ, if only we suffer with him so that we may also be glorified with him” (Rom 8:17).

Universal human experience affirms that the crosses some people bear are much heavier than our own. The pains of this life — or, to put it positively, the opportunities for redemptive suffering — are not distributed equally or even proportionately among humanity.

Yet Scripture also assures us that we are capable of carrying whatever cross God asks of us. We will receive strength to endure whatever comes our way (see 1 Cor 10:13).

St. Paul’s own example gives clear witness to the possibility of “offering up” our suffering for the benefit of others when he declares, “Now I rejoice in my sufferings for your sake, and in my flesh I am filling up what is lacking in the afflictions of Christ on behalf of his body, which is the church” (Col 1:24).

Our own suffering takes on a redemptive dimension when we unite it with the passion of Christ.

Suffering and Redemption

In his apostolic letter Salvifici Doloris (1984), which deals with human suffering and redemption, Pope St. John Paul II described the relationship between the two realities:

“The Redeemer suffered in place of man and for man. Every man has his own share in the Redemption. Each one is also called to share in that suffering through which the Redemption was accomplished. He is called to share in that suffering through which all human suffering has also been redeemed.

“In bringing about the Redemption through suffering, Christ has alsoraised human suffering to the level of the Redemption. Thus each man, in his suffering, can also be-come a sharer in the redemptive suffering of Christ” (No. 19, italics in original).

In the victim soul, such redemptive suffering takes on an intense, personal form, a gift of grace that is often accompanied by mystical phenomena.

Take, for example, the life of the Spaniard Sister Josefa Menendez (1890-1923), of the Order of the Sacred Heart of Jesus. She experienced a number of visions and locutions, along with seasons of excruciating physical and spiritual pain.

According to her diary, published under the title “The Way of Divine Love,” Sister Josefa was asked by Jesus to be a victim soul, a role she described this way:

“To be a victim necessarily implies immolation, and as a rule, atonement for another.

“Although strictly speaking one can offer oneself as a victim to give God joy and glory by voluntary sacrifice, yet for the most part God leads souls by that path only when He intends them to act as mediators: they have to suffer and expiate for those for whom their immolation will be profitable; either by drawing down graces of forgiveness on them, or by acting as a cloak to cover their sins in the face of divine justice.

“It stands to reason that no one will on his own initiative take such a role on himself. Divine consent is required before a soul dares to intervene between God and His creature. There would be no value in such an offering if God refused to hear the prayer.”

The Stigmata

Those who may not be familiar with the term “victim soul” may nevertheless have heard of one of its most spectacular forms: the stigmata, the crucifixion wounds of Christ, which typically appear on the body of the victim soul as bloody and unhealed wounds on the palms, feet, side or forehead.

Some stigmatists have been known to suffer periodically the crucifixion of Christ in a mystical way, bleeding and writhing in pain in a real-time experience of His passion and death.

Some have suffered the “invisible stigmata,” experiencing the pains of Our Lord’s passion without the apparent physical wounds.

St. Paul told the Galatians: “I bear the marks of Jesus on my body” (Gal 6:17). Though he may well have simply been referring to the scars of multiple floggings he had received for the Lord’s sake, some biblical commentators have speculated that the apostle may actually have borne the stigmata.

In any case, the first confirmed case of a stigmatist, and certainly the best known, is that of St. Francis of Assisi. He received the five wounds of Christ after a vision in 1224, two years before his death.

To date, 62 canonized saints and blesseds of the Church are known to have had the stigmata, and at least two dozen other claims of stigmata were reported in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Some examples of stigmatists of the past century:

St. Faustina Kowalska (1905-1938), the “Apostle of Divine Mercy,” suffered the “hidden stigmata,” the pains of crucifixion without the physical wounds, and offered up much pain and spiritual torment for the sake of sinners.

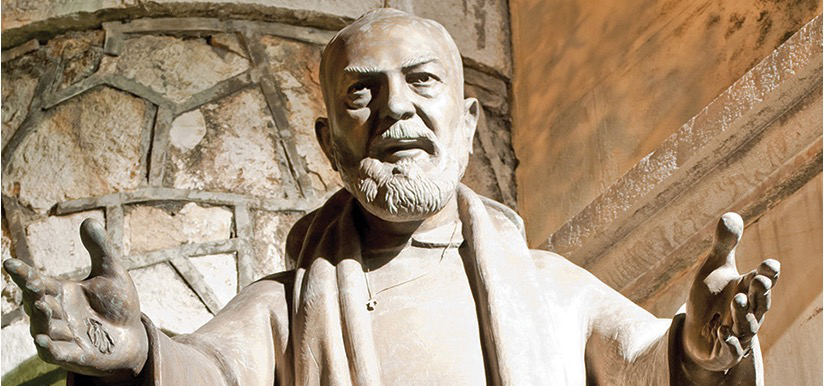

St. Pio of Pietrelcina (1887-1968), a Capuchin priest, was of poor health most of his life. He was a stigmatist who frequently was attacked by the devil both physically and spiritually, suffering intense pain of both body and soul.

Yet he was also a much sought-after confessor who could see inside a penitent’s soul and was credited with healings even during his lifetime. Bilocation, ecstasy and levitation were among the miraculous and mystical experiences associated with Padre Pio.

Theresa Neumann (1898-1962), bedridden with partial paralysis at age 20, received the stigmata in stages beginning in 1926. She had visions of Christ’s passion and experienced pain and wounds consistent with the crowning of thorns and crucifixion.

She reportedly bled from the hands, head and eyes during her Passion episodes, which were said to be at their worst every Good Friday.

Marthe Robin (1902-1981) was completely paralyzed by the age of 28. Incredibly, at 25 she was no longer able to take food, and at 26 she could not sip water. For the last half-century of her life, Robin survived solely upon the weekly Eucharist.

Immediately upon receiving the sacred Host, she would enter a mystical experience, or ecstasy, of the passion of Christ. The stigmata and the wounds of scourging and the crown of thorns would appear on her body.

Robin also was able to read a person’s soul, enabling her to give excellent spiritual advice, and she seemed to have very specific knowledge of events happening far from her.

Alexandrina de Costa (1904-1955), severely injured at 14 when she leaped out a window to avoid a rape at her home in Portugal, soon came to understand her suffering as her special vocation. By 25 she was completely paralyzed and spent all her time in prayer.

From 1938 to 1942, she suffered the mystical passion of Christ every Friday afternoon for three hours, during which time she would be able to move freely. Like Marthe Robin, she lived on the Eucharist alone for the last 13 years of her life.

Are We Obliged to Believe?

The Catholic Church does not officially designate anyone as a victim soul. The term stems, rather, from the testimony of those who have encountered Christians who seem to undergo the kind of redemptive suffering we have described.

The victim-soul status, even when it is genuine, is a matter of private revelation. Consequently, the Church teaches us that we are not obliged to accept, as part of the Catholic faith, the legitimacy of any particular person for whom such a claim is made, nor the genuineness of any mystical or miraculous claims that have been made in connection with such a person.

This includes even those people whose private revelations have been approved by the Church. (See the Catechism of the Catholic Church on this subject, No. 67).

Nevertheless, the fundamental spiritual truth — illustrated so vividly by the notion of a victim soul — still remains: We can accept the pain and suffering of this life with patience and love for the intentions and benefit of ourselves and others in the Communion of Saints.

Gerald Korson, an editor and Catholic journalist for more than 25 years, writes from Indiana.