Except for such widely known celebrations as Easter, Christmas and Pentecost, most lay Catholics lump all Church celebrations under the term feast or feast days.

While the terminology is not necessarily incorrect, feasts are only one of the three categories of such celebrations in the Church year; the other two are solemnities and memorials. But what’s the difference? The Church has always provided the faithful people of God with externally expressed devotions, festivals and celebrations through which they may pay homage to the Creator. These holy activities are not merely random events, but follow a seasonal, regulated schedule established by the Church’s liturgical calendar. The day-to-day events of the annual Church year are primarily catalogued as a solemnity, a feast or a memorial.

In the fourth century, Emperor Constantine ended the Roman persecution of all religious factions and claimed Christianity to be the state religion of the Roman Empire. As the Church and Christian faith expanded, the number of religious celebrations subsequently increased. Unfortunately, for centuries there was no centralized control over the observance of the many celebrations. Every diocese had its own calendar, therefore rituals differed, celebrations honoring the mysteries of sacred Scriptures competed with honoring a saint, feast days overlapped, and almost every Sunday liturgy was pre-empted by a special occasion. This all led to confusion and abuses that continued until the reforms of the Council of Trent (1545-1563) and the eventual development of a universal calendar.

A churchwide calendar prompted the need to effectively organize the numerous holidays in a manner applicable to every diocese. A most challenging aspect of this effort was the standardization of the rituals used during the different ceremonies and, further, the sorting out and assigning of common dates or time frames to each event. A well-organized liturgical calendar did not happen overnight, but has evolved over the past 450 years. While the methods of categorizing the various festivals have varied, the Church has been consistent in her effort to arrange the events according to importance. The birth of Jesus is considered more important than the birth of John the Baptist; the birth of the Baptist more important than the dedication of St. John Lateran church; the life of the Blessed Mother outranks that of St. Francis of Assisi; and so on. The hierarchal process used as recently as the 20th century rank, or order, Church celebrations by calling them doubles of the first class, doubles of the second class, greater doubles, lesser doubles, simples and commemorations. In 1962, they were called first class, second class, third class and commemorations. The Second Vatican Council simplified the classifications to solemnities, feasts and memorials.

Solemnities

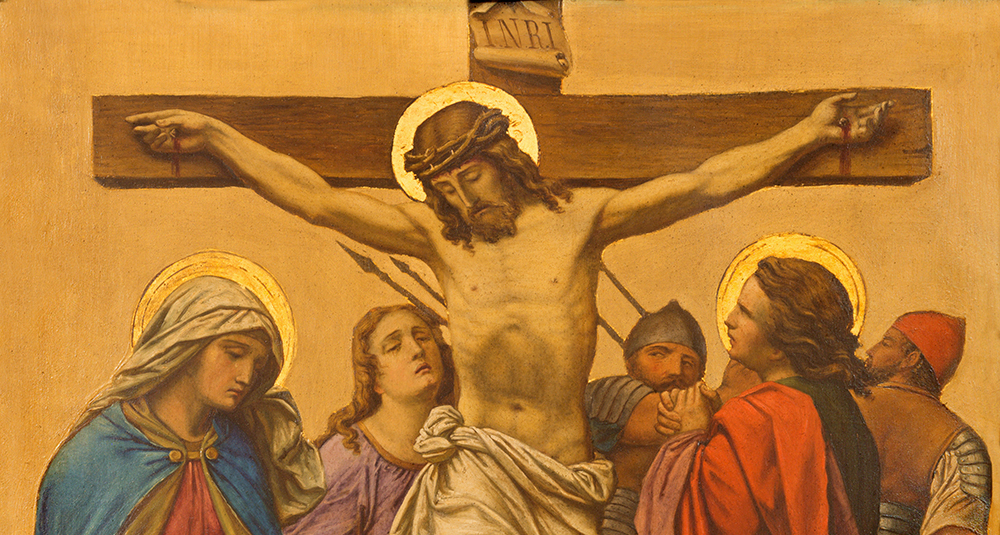

A solemnity holds the highest rank among Church celebrations and there are 24 days so marked on the annual liturgical calendar. It is a day that recalls and glorifies an important event in the life of Jesus and the most significant mysteries of the Catholic Christian faith: Christmas, Epiphany, Easter (the Easter Octaves including Divine Mercy Sunday), Pentecost, Holy Trinity, Ascension, Corpus Christi, Sacred Heart, Christ the King. So, too, honored as a solemnity are the days associated with the Blessed Mother: the Immaculate Conception, the Assumption, the Annunciation and Mary, Mother of God. Some saints are acknowledged with a solemnity: St. Joseph, the Nativity of St. John the Baptist, Sts. Peter and Paul and All Saints Day.

In addition to every Sunday, the Catholic Church prescribes holy days of obligation, which include certain solemnities. In the United States there are six holy days of obligation: Mary, Mother of God, the Ascension, the Assumption, All Saints, the Immaculate Conception and Christmas. While all holy days of obligation are solemnities, not all solemnities are holy days of obligation. For example, the celebration of the Immaculate Heart of Mary is a solemnity but not a holy day of obligation. The same is true of the solemnity of St. Joseph and the solemnity of Sts. Peter and Paul.

Some solemnities are always celebrated on the same calendar date and are known as “fixed” on the liturgical calendar — for example, Dec. 25 is always the date of Christmas, Nov. 1 is the date of All Saints and the Immaculate Conception is always on Dec. 8. Other solemnities are “moveable” — that is, their dates change or move based on the date of Easter. Pentecost is 50 days after Easter, Holy Trinity is the first Sunday after Pentecost, Corpus Christi is the second Sunday after Pentecost, the Sacred Heart of Jesus is the first Friday after Corpus Christi and so on.

So, just what distinguishes a solemnity? The celebration begins with evening prayers on the day before and some, if a holy day of obligation, have a vigil Mass. If the solemnity falls on a weekday, the daily Mass looks much like a Sunday liturgy, including three readings, the Gloria and the Creed. All the prayers of the Mass reflect on the event or person being celebrated. These added liturgical elements help to embellish the special attention given the event or person.

Feasts

Celebrations identified on the Church calendar as a feast typically honor a special saint, such as one of the apostles. Other saints assigned a specific feast day include Sts. Simon and Jude, St. Stephen, the Holy Angels. Important events in Christian history are likewise identified as feasts: the Baptism of the Lord, the Conversion of St. Paul, the Transfiguration, the Visitation, the Presentation of the Lord, the Holy Family, the Birth of Mary, the Dedication of the Basilica of St. John Lateran in Rome, the Holy Innocents, the Triumph of the Holy Cross, and the Chair of Peter. A feast that falls on a weekday is not preceded with a vigil Mass, the Creed is not obligatory and most feasts are fixed dates on the calendar.

Memorials

The third category of celebrations and those most representative of what we call “feast days” are properly known as memorials. Memorials are identified as either obligatory, those that must be celebrated universally on an assigned day, or optional, meaning it is up to the celebrant as to whether that particular saint is celebrated. All memorials are fixed on the annual calendar. Memorials most often honor and focus us on the pious life of a saint. If Scripture mentions the particular saint, then the Mass readings on that day are taken from the applicable Scripture, such as, on the obligatory memorial of St. Martha the readings are from John (chapter 11) or Luke (chapter 10). If the saint is not mentioned in Scripture, then the readings are the ordinary, or normal, readings assigned for that day.

Optional memorials often identify a saint special or familiar to a particular location or religious order, but are often those not necessarily well known throughout the worldwide Church. For example, Sept. 19 is the optional memorial to St. Januarius, the patron saint of Naples, Italy. While the people of Naples and the surrounding area may well remember and acknowledge Januarius, a parish in another part of the world may not. The local parish priest normally decides about recognizing optional memorials.

As every country honors her founding fathers, her national heroes, independence day, and other national events, so does the Church celebrate the great sacred mysteries — the life of Jesus, the Blessed Mother, the saints and the martyrs who died for the faith. The Church classifies each celebration according to its importance and ranks them on the annual liturgical calendar as a solemnity, a feast or a memorial.

D.D. Emmons writes from Mount Joy, Pa.

Ferial Days

If we look carefully at the Church liturgical calendar, there are some days that have no celebration assigned; no solemnity, no feast, no memorial. Such days are known as a “ferial” days, from a Latin word meaning free. In ancient Rome the term referred to a holiday, especially for slaves.

On the liturgical calendar, a ferial day is always on a weekday, Monday through Friday, and occurs during Ordinary Time. On that day the priest has the option of celebrating the previous Sunday Mass, a votive Mass or a Mass acknowledging any saint he desires. The celebrant may select the readings or use those appointed in the Lectionary for that day.

Sunday

The documents of the Second Vatican Council reflect on the importance of Sunday: “The Lord’s Day is the original feast day.… Other celebrations, unless they be truly of greatest importance shall not take precedence over the Sunday which is the foundation and kernel of the whole liturgical year” (Sacrosanctum Concilium, No. 106).