Parables are perhaps the best-known aspect of the Lord’s teaching in the New Testament, but in this He accommodated himself to patterns of teaching already in use at the time.

In the Old Testament, God commanded Ezekiel to teach Jewish exiles in this manner (see Ez 17:3-21; 19:1-14). Here the prophet was employing the Hebrew genre mashal. The genre appears in older settings (Jdg 9:7-15), but probably the best known is the mashal of the ewe lamb that the prophet Nathan used to convict David of his murder of Uriah the Hittite (2 Sm 12:1-4).

What is a mashal? A mashal is usually translated as “riddle,” but really it is less a brainteaser than an allegory told with different levels of meaning, with each element corresponding to a real life referent — here, the “rich man” is David, the “poor man” Uriah and the “ewe lamb” Bathsheba.

The Good Shepherd. Renata Sedmakova / Shutterstock.com

Parables can be very short, proverbial and aphoristic. Luke 5:36 and 6:39, for instance, are simply pithy, memorable sayings. In fact, in Luke 4:23, what the Revised Standard Version Bible and New American Bible translates as “proverb” is parabole in the Greek.

More common, however, are the extended parables that involve several different aspects of comparison — for example, Matthew 7:24-27 and the parable of the two houses, one built on sand and the other on rock. The Lord — unlike his hypocritical opponents — actually puts into effect His own advice, choosing a rock named Peter on whom to build His house the Church (see Mt 16:16-18).

The parables of Jesus in Matthew highlight theological themes found only in the first Gospel. The well-known parable of the wheat and the weeds (see Mt 13:24-30) and the more concise parable of the fishnet (Mt 13:47-50), both serve to underscore the Church as a mixed body consisting of both saints and sinners whom God will providentially leave in place until the time of the great eschatological separation.

Even parables common to more than one Gospel are recorded differently by each of the Evangelists. Some, like the parable of the wicked tenants are understood by friend and foe (see Mt 21:45; Mk 12:12; Lk 20:19). But the misunderstanding motif figures enormously in Mark’s version of the parable of the sower (4:1-20). Most homilists will take the view that the parable concerns our receptivity to the Word of God. But I am afraid this is a case in which the homilists have allowed the more familiar versions of the story in Matthew and Luke to color their reading. In the context of Mark, thus far there has been a great deal of opposition to Jesus and very little receptivity. Even the disciples of Jesus who have followed Him do not understand Him and demonstrate fear and unbelief (Mk 4:12-14; 4:40; 6:50-52; 7:17-18; 8:17-21). They have received the mystery of the Kingdom all right, but apparently not the knowledge and understanding that must come with it (compare Mk 4:11 and Mt 13:11).

Jesus’ Approach

The Gospel of Mark’s ironic introduction to parables begins in 4:10. Jesus is asked why He teaches in parables. What is striking is that He does not respond the way we imagine that He should, with something like, “Parables are my way to use earthly similitudes to convey heavenly realities because such analogies are the only things earthly human beings can understand.” Astonishingly, Jesus himself explains that parables are not to teach anyone anything at all, but rather to confound and confuse and to separate the insiders of Jesus from the outsiders for whom parables will be opaque (see 4:11-12).

The Laborers in the Vineyard. Shutterstock

But if this is the case, why should the disciples of Jesus have needed an explanation of the parable at all? “Do you not understand this parable? Then how will you understand any of the parables?” (Mk 4:13). In the context of Mark, the disciples are little more secure than the enemies of Jesus who are confounded by his message. How often in real life have we seen the irony of supposed Church insiders not getting the message at all?

What is going on here is that our understanding of parables is being challenged. In this instance, it is not really about our response at all, or, more precisely, it is about the fact that in spite of the opposition of enemies of the Kingdom and in spite of the moral and intellectual failings of the Kingdom’s putative friends, the Kingdom will succeed immensely in the end. Even though most of the seeds sown by God seem to be failing, the ones that do take root will bear abundant fruit. In other words, the parable is, first, Jesus’ explanation of why the apparent failure of His ministry is, in fact, part of God’s plan — much as Isaiah’s original mission was to harden hearts for a time (see Is 6:9-13). Second, the apparent failure of the kingdom proclamation will be the seeds of its success. We could even say that not only is the parable of the sower a parable about the kingdom proclamation of Jesus, but it is a parable about parables.

The Prodigal Son

The parable of the sower shows us that we should be a little more careful about naming parables than we usually are. This parable could have been called the parables of the seeds or the parable of the soils, and each name would subtly affect our interpretation. But nowhere is the name we impart to the parable more powerful to affect our construal of it than in the parable of the prodigal son (see Lk 15:11-32).

Unlike the aphoristic parables or even the more extended ones such as the mustard seed (see Mk 4:30-32), this one has a complete story line and most of us know its basic outline. A son sells all his goods and runs away from the family, squandering his precious inheritance in the process. But then, realizing the self-imposed squalor of his condition, he repents, and his overjoyed father runs halfway down the road to meet him. The father gives him a great celebratory banquet, delighting that his lost son has now been found. From the classic spiritual “Amazing Grace” to countless homilies, this parable of repentance has piqued the religious imagination of Christians of all stripes down through the centuries.

But perhaps the repentance and joyous acceptance of the Father is not the parable’s most important theme. Often left out entirely from reflection is the anger of the elder brother, who thinks he has received nothing for his years of fidelity while his lesser, disobedient sibling is welcomed back to the family on an equal basis. The parable of the prodigal son, in fact, could be more aptly named the parable of the elder brother. Read in its entirety, the parable of the prodigal son seems like an expansive retelling of Matthew’s parable of the two sons (see Mt 21:28-32). In both cases the parables are Jesus’ thinly veiled commentaries on the state of affairs in the Church with the younger brother as a stand-in for the wayward Gentiles — welcomed back to the people of God after centuries of dissolution and rebellion — and the elder brother representing Jewish Christians, upset that their long-held privileged position in the family is being compromised.

But whatever we call it, Luke’s parable of the elder brother is among the most famous in the Jesus tradition. Indeed, as the state of Idaho’s motto is “Famous Potatoes,” Luke’s Gospel’s motto should be “Famous Parables.” It is only Luke who contains the well-known parables of the accursed fig tree (see 13:6-9), the rich man and Lazarus (16:19-31) and real sleepers like the parable of the widow and the unjust judge (18:1-8). By far the most famous of the special Lucan parables is that of the good Samaritan.

The Good Samaritan

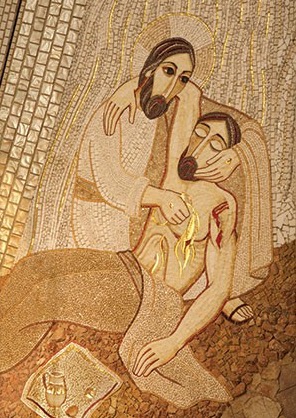

The Good Samaritan. Renata Sedmakova / Shutterstock.com

On a surface level, the message of this one is easy to grasp — the true love of neighbor will be shown by the one who actually extends mercy (in this case corporal mercy) — and not necessarily by the professional religious. But a fuller understanding of the good Samaritan must include the degree to which the parable is profoundly subversive of the religious assumptions of Jews living in Palestine for whom a “good Samaritan” was a contradiction in terms and actually rather scandalous.

But whether they scandalize or challenge us, motivate or frighten us, we encounter the heart of Our Lord’s teaching in the parables and thus the mind of the Lord himself. The style of the teaching wasn’t unique, but the Divine Person whom we encounter is!

Dr. Peter Brown earned his doctorate in Scripture from The Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C. He serves as academic dean of the Catholic Distance University.