If you’re aware of King Arthur and his Knights of the Round Table — if you’ve heard Richard Wagner’s opera Parsifal or seen movies such as “Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade” — you’ve heard of the Holy Grail.

That object of quest and romance, providing supernatural nourishment and healing, has a long history in literature and legend. Tales about the Holy Grail — as a stone or gem, as the chalice Jesus used, or as the platter on which the Passover lamb was served at the Last Supper before Jesus suffered and died on Calvary — appeared in French, English, German and Italian during the 12th and 13th centuries. The stories include mysterious connections with Joseph of Arimathea, the spear of Longinus (the centurion who pierced Christ’s side on the cross) and even the conversion of England. The Grail was also sometimes described as the cup in which Joseph of Arimathea caught the blood and water that poured from Christ’s side after Longinus pierced Him as He hung dead on the cross, a mysterious sign of the Sacraments of Baptism and the Eucharist and their source in the Sacred Heart of Jesus.

In these early versions of the quest for the Holy Grail, the imagery clearly reflects Catholic belief in the real presence of Jesus Christ in the Precious Body and Blood of the Holy Eucharist. In spite of all these sacramental and doctrinal images and interpretation, the Catholic Church in the Middle Ages did not participate in or emphasize the quest for the Holy Grail. While the medieval Church is often criticized for taking advantage of miracles and shrines for pilgrimage, she did not use this seemingly perfect opportunity for donations and bequests to venerate the Holy Grail, among other relics of Jesus’ life and passion. Yet, in the same era, the Church developed even greater devotion to the holy Eucharist through the institution of the Solemnity of Corpus Christi, the Body and Blood of Christ, in 1264. Pope Urban IV asked St. Thomas Aquinas to write the Divine Office for this great feast, and he composed the great hymns and sequences we sing today on Holy Thursday and Easter Sunday and at Benediction of the Blessed Sacrament. The legend of the Holy Grail coincides with this focused devotion and adoration of the Blessed Sacrament, which including the Corpus Christi processions.

Journeys of the Grail

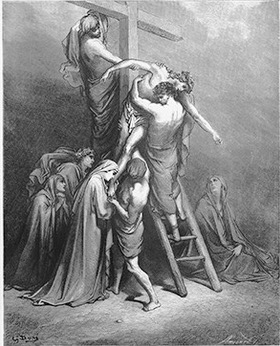

The story of the Holy Grail begins with Joseph of Arimathea, the member of the Sanhedrin who went to Pontius Pilate for permission to remove Jesus’ body from the cross on Good Friday. Joseph and Nicodemus — who had come to Jesus secretly — prepared His body for burial in Joseph’s own new tomb. Imprisoned by the Jewish authorities for his proclamation of Jesus’ resurrection, according to the apocryphal Gospel of Nicodemus, Joseph receives the Grail from our Savior to nourish him — then miraculously escapes from his cell without disturbing the seals on the door. Leaving the Holy Land, he travels to France and then to England, bringing the Grail with him to Glastonbury in Somerset, England. As Glastonbury is also claimed by some legends to be the burial place of King Arthur and his queen, Guinevere, the legends of Avalon or Camelot and the Holy Grail become entwined.

The Holy Grail of Arthurian legends becomes the great object of a chivalric quest, as the Knights of the Round Table set out to find the chalice and the Holy Blood (the sangreal) — and fail or succeed according to their purity and holiness. Thus the great Lancelot fails because of his adulterous affair with Guinevere, while Percival, Bors or Galahad, depending on the version, succeed because of their purity, or in the case of Galahad his virginity. Literary historians have often surmised that the ideals of chivalry were inspired by medieval devotion to the Blessed Virgin Mary. Arthur’s knights strove to be brave, to defend women, and to be chastely devoted to their chosen Lady. When a knight failed in this ideal, as Sir Lancelot failed, the Holy Grail became a catalyst for his repentance as he recognizes his unworthiness and does penance for his sins of adultery and disloyalty.

Although Thomas Malory’s 15th century Le Morte d’Arthur included the quest for the Holy Grail in his influential summation of the Arthurian legends, the fascination of the Grail legend faded at the end of the Middle Ages. The story of the Holy Grail was revived by Romantic and Victorian era interest in what many called the “Age of Chivalry,” with Alfred, Lord Tennyson’s “Idylls of the King” (1869) and Richard Wagner’s Bayreuth festival piece Parsifal (c. 1880), although both the Anglican Tennyson and the mystical Wagner eliminated the background of the Real Presence in their Grails. In the 20th century, “Monty Python and the Holy Grail” tells a ridiculously comic version of King Arthur’s knights and their quests, while John Boorman’s 1981 film, “Excalibur,” based on Thomas Malory’s work, included Percival’s successful quest for the Holy Grail, healing Arthur and the land because “the land and the king are one.”

Myths and Theories

Joseph of Arimathea removes Jesus from the cross. Shutterstock

This mysterious link between the legend of the Holy Grail and Britain, or England, became an argument for the English Reformation in the 16th century. Queen Elizabeth I cited Joseph of Arimathea’s presence in England long before Pope St. Gregory the Great sent St. Augustine of Canterbury to Kent as important to the tales. She informed the Catholic bishops who protested against the establishment of the Church in England at Parliament in 1559 that Joseph of Arimathea was the “first preacher of the Word of God” in England, and that the country already had bishops and priests when Rome “usurped” their authority. Elizabeth was citing the authority of the sixth-century monk Gildas, whose shrine at Glastonbury Abbey had been destroyed when King Henry VIII suppressed all the monasteries, convents and friaries in England, Wales and those parts of Ireland he ruled.

Near the ruins of Glastonbury Abbey today, the annual Glastonbury Festival celebrates music and New Age, neo-pagan spirituality during the summer solstice. Although the most reliable historical research indicates that Glastonbury Abbey was founded in the seventh century, the legends of King Arthur, Joseph of Arimathea, the Holy Grail, Avalon and even the Glastonbury Thorn, a tree that magically grew from Joseph’s staff, become a confusing tangle of mystery and secret knowledge.

Conspiracy theorists have even woven the legend of the Holy Grail into their webs of arcane and unknowable history, presenting a story that Dan Brown infamously adopted in “The Da Vinci Code.” This version claims that the Holy Grail was really the womb of Mary Magdalen, or her descendents from her marriage with Jesus, who had not really died on the cross, nor risen from the dead — and who, according to Brown and his sources, is not really the Incarnate God, the Second Person of the Trinity, who came to earth to redeem us and establish His Church.

The Real Presence

As noted in the 2006 book “The Grail Code: Quest for the Real Presence” (Loyola Press), Adolf Hitler did search for the Holy Grail just as “Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade” depicts. He and Heinrich Himmler were fascinated by the promise of great and secret powers they could obtain by possessing the Grail; Hitler believed the blood of the Grail was the original, pure Aryan blood. Himmler, according to “The Grail Code,” was “nuts for Grail lore and the Arthurian legends in general” (p. 223), and he both re-created the Round Table at the SS headquarters and searched for the Holy Grail in southern France, the enclave of the medieval Cathars, Gnostic heretics who surely would not have valued the Holy Grail in connection with the Eucharist. The Cathars rejected belief in the Real Presence in the Eucharist because of their absolute dualism, believing that all matter is evil, and since each of the seven sacraments involve matter (bread and wine, water and oil, etc.), they refused baptism and all the human elements of the Catholic Church.

But all these false views of the Holy Grail cannot diminish the true mystery of the real presence of Jesus Christ in the holy Eucharist. We have found the Holy Grail; Jesus Christ gave it to the Church the night before He died and told the apostles to “do this in memory of me” (Lk 22:19). At every Mass the words of consecration make the Lord present in holy Communion, our sacramental source of nourishment and healing.

Stephanie A. Mann writes from Kansas.

Thomas Aquinas and the Grail

When he wrote the Divine Office for the Solemnity of Corpus Christi, St. Thomas Aquinas also wrote prayers to prepare for and rejoice after receiving holy Communion. As the Holy Grail healed and made whole the knight who was worthy to find and receive it, St. Thomas shows how much we need the healing grace of holy Communion: “Almighty and ever-living God, I approach the sacrament of Your only-begotten Son Our Lord Jesus Christ, I come sick to the doctor of life, unclean to the fountain of mercy, blind to the radiance of eternal light, and poor and needy to the Lord of heaven and earth. Lord, in your great generosity, heal my sickness, wash away my defilement, enlighten my blindness, enrich my poverty, and clothe my nakedness. May I receive the bread of angels, the King of kings and Lord of lords, with humble reverence, with the purity and faith, the repentance and love, and the determined purpose that will help to bring me to salvation. May I receive the sacrament of the Lord’s Body and Blood, and its reality and power. . . . Amen.”

Like knights of old we seek the Holy Grail, finding it at Mass each Sunday or weekday, praying to be prepared to receive the Lord’s Body and Blood worthily and devoutly.