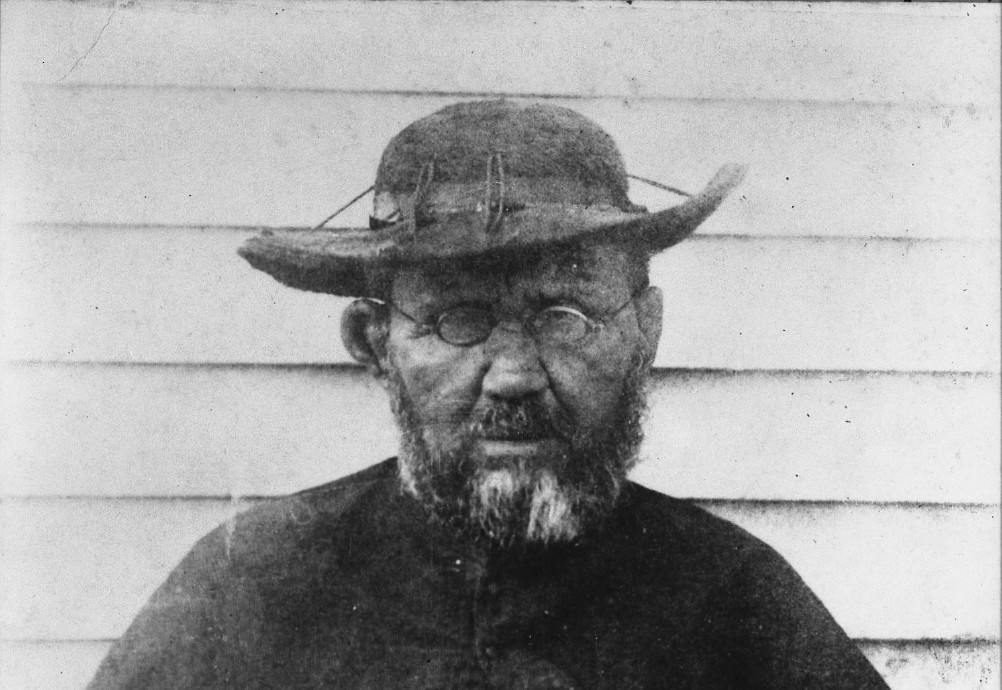

Jozef De Veuster (1840-1889) was once a gregarious boy who loved life — even a skating champion near his Tremelo, Belgium, hometown. Brought up in a faithful family, he chose to follow in the footsteps of his older brother and entered religious life with the Congregation of the Sacred Hearts of Jesus and Mary in 1859. Better known by his religious name, Damien, this saint had the heart of a missionary and was known to pray each day to become one. In 1863, Damien volunteered for Hawaiian missions in place of his sickly priest-brother who was supposed to go. Soon, his zeal for souls earned St. Damien De Veuster the title “apostle to the lepers,” and ultimately led to his canonization by Pope Benedict XVI in 2009.

Damien arrived in Honolulu in 1864 and was ordained a priest that May. He spent most of the next decade joyously pastoring his flock. Things changed, though, when many islanders — including many from Damien’s own flock — contracted leprosy. Then thought incurable, the ancient disease of leprosy came in a few different forms, the most widespread of which was an ongoing decay of the living human body. The lepers were taken from their homes and assigned as outcasts on the island of Molokai, never seen again by their families. A slow painful death awaited them.

Hawaiian Bishop Louis Maigret strongly desired priests to minister on the island and asked for volunteers since he knew the assignment was equivalent to a death sentence. Damien joyfully and heroically offered himself, leaving for Molokai on May 10, 1873. Since he couldn’t live with the lepers for fear of infection, Damien found shelter under the indigenous pandanus tree for quite a while after his arrival.

For 16 years, Damien ministered as a loving father among those doomed to death. For them, he celebrated the sacraments, gave structure to the community, erected housing facilities and bandaged wounds. And the lepers didn’t just suffer physically. Totally shut off from the world, they awaited their fate, and most saw no point in their suffering. Knowing they came to Molokai to die, the lepers often gave into lewd and sinful behavior. Damien challenged them to be better.

Damien’s primary role was to lead the lepers closer to Christ, and that required giving them hope. In what could be an easily overlooked aspect of his work on Molokai, Damien gave a hopeful new perspective to the “living dead” by digging graves so the dead of Molokai would have a dignified burial. Damien showed the lepers that their bodies deserved dignity, even in death. Their suffering was transformed to have purpose, and this led them along the path of hope in eternal life. By the time Damien died, the majority of the island was Catholic.

In 1888, Damien was joined in his ministry to the lepers by St. Marianne Cope and other Sisters of St. Francis from Syracuse, New York. Eventually canonized herself, Cope cared for Damien when he became a victim of leprosy. He died at age 49 on April 15, 1889, already an internationally acclaimed humanitarian. Originally buried under the tree where he slept his first nights on Molokai, his remains were moved to his homeland in 1936 at the request of the Belgian king.

Damien passed up many opportunities to leave Molokai, ever zealous to win souls for Christ. He wrote to his brother: “People pity me and think me unfortunate, but I think of myself as the happiest of missionaries.” Damien’s sacrifice was an embodiment of Christ’s, “No one has greater love than this, to lay down one’s life for one’s friends” (Jn 15:13). Of this, Pope St. John Paul II remarked at Damien’s 1995 beatification, “What could he have offered the other lepers, who were condemned to a slow death, if not his own faith and this truth that Christ is Lord and that God is love? He became a leper among the lepers; he became a leper for the lepers. He suffered and died like them, believing that he would rise again in Christ, for Christ is the Lord!”

His feast day is May 10.

Michael R. Heinlein is editor of Simply Catholic.