‘Jesus became what we are that he might make us what he is.’

Church and state were intertwined when the Emperor Constantine legalized Christianity in 313. While it meant Christians no longer were persecuted, new challenges and difficulties awaited believers. Resolution of doctrinal arguments was now a political problem as much as anything. At best, such theological clashes meant that Christians would not talk to each other and, at worst, they killed each other.

These disputes touched the very heart of Christian faith, such as the heresy of the priest Arius, who taught that Jesus Christ was not consubstantial with God the Father. While denounced at the Council of Nicaea in 325, his teachings did not die soon enough. His and other heresies debated at other councils enmeshed much of the life of the early Church.

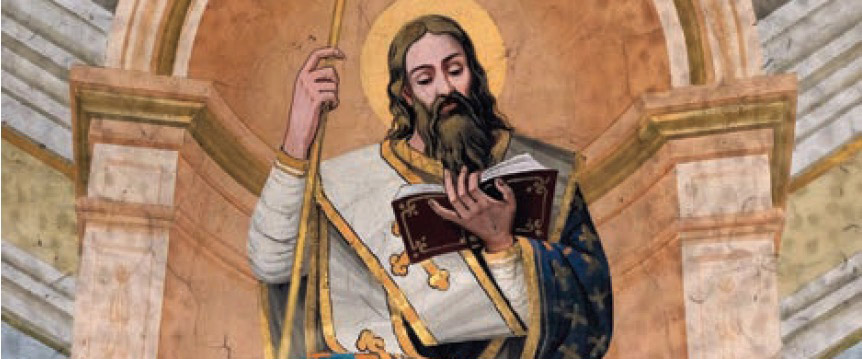

St. Athanasius (296-373) was perhaps the staunchest defender of the truth about Jesus Christ in this age: that he was truly the Son of God, being fully God and fully man. Arius’ heresy had attracted many followers, many of whom were bishops. Athanasius was among the intellectually capable leaders the Church needed to articulate the truths of Christianity in conformity with revelation. But it came with a great cost. He faced hatred, lies and personal attacks. He risked imprisonment and even death. At times, it looked like the whole world was against Athanasius — all because of his zealous apostleship in defense of truth and desire to preserve the Church’s unity. He teaches us the importance of swimming against the tide for the sake of truth.

Defending doctrine meant making enemies. This created political problems for preachers and teachers such as Athanasius. Expelled five times from his flock by emperors for his outspoken defense of truth, his life was not easy or comfortable.

Shortly after he was named bishop of his home diocese — the metropolitan see of Alexandria in northern Africa — attacks against Athanasius began. Exiled as a scapegoat for infighting among Christians, Athanasius corresponded with his people by letter, reiterating to them that his suffering was for the sake of truth. When Constantine died in 337, the deceased emperor’s sons reinstated Athanasius to his native place.

Back in his diocese, Athanasius was forced to confront problems created by a rival bishop in Alexandria, Eusebius of Nicomedia, who was an intellectual disciple of Arius and who had baptized Constantine. After appealing to the pope for assistance, Athanasius found an ally who wanted to prevent Arius’ heresy from being imposed on the entire Church. Other non-Arian bishops wanted to find a middle ground and to depose Athanasius.

Ten harmonious years of fruitful ministry followed for Athanasius among his people. Liturgies were crowded, religious life blossomed, and Athanasius produced an expansive body of spiritual writings.

That came to a halt in 356, when Emperor Constantius incited a revolt in Alexandria with the hope of removing Athanasius. He escaped, governing his diocese from a distant monastery, with a price on his head. The faithful in Alexandria lived under a reign of fear for about a year and a half until Constantius died.

In 362, Athanasius returned to Alexandria under Julian the Apostate’s leniency. Julian abandoned his earlier objectivity and, intimidated by the untiring apostolic activity of Athanasius, quickly sent him from Alexandria. Yet again, Athanasius was a marked man. Athanasius returned to Alexandria, only to be exiled again by the new emperor — only for a brief time, however, since he realized it was not politically expeditious.

After seven peaceful years in Alexandria, St. Athanasius died in 373. His feast is May 2.

Michael R. Heinlein is editor of OSV’s Simply Catholic and a graduate of The Catholic University of America. He writes from Indiana. Taken from Our Sunday Visitor’s ‘Saints in Times of Crisis’ booklet.