Almost as soon as a person begins any serious exploration of the Christian heritage, he or she invariably runs across references to “the Fathers of the Church,” or the “early Church Fathers.”

One gets the clear impression that these people are important. Protestant, Orthodox and Catholic writers all tip their hats to them. Official documents of the magisterium extol their authority (see, for example, Dei Verbum, No. 23).

But often the reader is left a bit bewildered. Who precisely are the Fathers of the Church and why do they matter? And if they are so important, what’s the best way to get started learning about them?

First of all, let’s make it clear who the early Church Fathers are not. The apostles and other heroes of the New Testament era stand in a class all their own. They are not regarded as Church Fathers. Neither are great theologians and Doctors of the Church from medieval or modern times, such as St. Thomas Aquinas.

So, if these venerable writers are not Church Fathers, who are, and why do they bear this title? “Church Father” is not a formally conferred title, as is “Doctor of the Church.” There is no complete, official list of the Fathers. Instead, the designation results from popular acclaim and long-standing tradition that came about in this way: In ancient times, teachers were commonly regarded as intellectual fathers. Some early Christian teachers put their teaching into writings that continued to guide the community of the faithful long after their passing. In disputes over doctrine and the proper interpretation of Scriptures, these early writers were cited as “the fathers” or “the Fathers of the Church.” This popular title stuck and the designation over time was expanded to refer to all the great orthodox Catholic authors writing about faith and morals from about A.D. 100 to about 800.

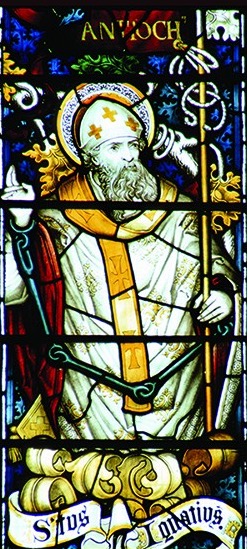

St. Ignatius of Antioch Shutterstock

This time period is not as arbitrary as it may seem. It is roughly coterminous with the first seven ecumenical councils of the Church, which defined and defended the two most fundamental dogmas enshrined in the Creed — that we believe in one God in three persons, and that Jesus Christ, the savior of the world, is true God and true man. This is the time period in which the canon of Scripture was clarified and the great liturgical traditions of the Church — including Roman, Byzantine and Maronite — took their distinctive form.

The Catholic teachers and writers of this period played a role that can never be played again, transmitting and witnessing to the ancient apostolic tradition and giving a decisive, classic shape to that heritage.

Most of these writers were saints. Some of them, such as Tertullian, fell noticeably short. Saint or not, none of them are personally infallible. If they should agree on anything, it would be rather remarkable, since this disparate group spans seven centuries and three continents. But their teaching does agree on a great many points, and this is a testimony that such teaching did not originate with them, but is rather being passed down to us through them. It is in their consensus (consensus partum) that the Church, from the earliest times, has regarded them as infallible commentators on Scripture and the unwritten apostolic tradition.

Their importance to apologetics and dogmatic theology goes without saying. When people claim that devotion to Mary is a medieval invention, you can conclusively prove otherwise simply by going to the Fathers of the Church. The same can be done when Jehovah’s Witnesses allege that Constantine invented the divinity of Christ.

But just as we read Scripture for more than apologetics purposes, so with the Fathers. We would agree with the late Cardinal Jean Daniélou, S.J.: the Fathers “are not only the truthful witnesses of a bygone era; they are also the most contemporary nourishment of men and women today.” One of the greatest ways to grow in the spiritual life and be imbued with the Catholic spirit is to read the writings of the early Church Fathers. In approaching their work, we should not simply be looking for information, but formation — to receive from them an authentically Catholic vision and a truly passionate zeal for holiness.

Where to Begin?

But then comes the next problem. A lot can be written by hundreds of men over 700 years. St. Augustine alone wrote more than 4 million words. One medieval monk quipped, “He who says he has read all of Augustine . . . lies!”

So, how can we get started in reading the Fathers? Where is the best place to begin?

Fortunately, a reading plan has already been laid out for us by the Church. In the revision of the Divine Office mandated by the Second Vatican Council, the late-night hour of “vigils” was transformed into the Office of Readings which can be done at any hour of the day. For each day, it includes one of the longer psalms, broken up into three parts; a page-long reading from the Bible; and a non-biblical reading about a page long, most usually from one of the early Church Fathers. This patristic excerpt is either a commentary on the biblical reading, the liturgical season or the saint of the day. Thus the Office of Readings is a ready-made collection of, as it were, the Fathers’ greatest hits, an introduction to the most accessible, inspirational and instructive nuggets from the patristic gold mine.

Intimidated by the complexity of the Divine Office? Not to worry. The Office of Readings is rather simple to follow and is more easily accessible than you might think, both in print and electronically (see sidebar). It is the most accessible entry into the world of the Fathers.

What’s Next?

So you’ve read and loved the excerpts and are now ready for entire works. Now what do you do?

Begin at the beginning. The “Apostolic Fathers” are the earliest of the Fathers and are known as apostolic because their life span overlapped to some degree the life span of at least some of the apostles. In some cases, there is evidence that some of these Apostolic Fathers, notably St. Polycarp, had personal contact with an apostle.

St. Augustine (Renata Sedmakova/Shutterstock.com)

Beyond the simple fact that they came first and laid the foundation for later Fathers, there are two other good reasons to start with them. One is that they have undisputable apologetic value as witnesses to unwritten apostolic tradition.

Second, they are, for the most part, simple, pastoral men like the apostles and are therefore easy to understand. You don’t need to take a course in Platonic philosophy to make sense of their writings. In fact, many of the documents of this period follow the same basic format as what we’re already familiar with in the New Testament — pastoral letters and “acts” of the martyrs.

Of course, it would be helpful to read a brief bit of background before delving right into the documents. There are several convenient sources of such information. But beware of making the mistake of spending so much time preparing that you never actually read the texts. The great thing about the Apostolic Fathers is precisely that there really aren’t too many necessary prerequisites to reading them.

With all due respect to my dear Jesuit friends, the original St. Ignatius (d.c. A.D. 110) was not the one from Loyola, but from Antioch. He is without a doubt the most passionate and inspiring among the Apostolic Fathers, the easiest author to read and to share with others. He was the second bishop of Antioch after the apostles, witness to the tradition of Sts. Peter, Barnabas and Paul. It was probably only about 15-20 years after the final edition of the Gospel of John that Ignatius was arrested and sentenced to die for his faith in Rome. He was marched overland from Syria through what is now western Turkey all the way to Troas (Troy) where he was put on a ship to Italy. As he passed through the Asian countryside, he wrote short letters to the various congregations of the region. They provide a fascinating window into the soul of a martyr, a fiery testimony of the love that drove the martyrs to lay down their lives as witnesses to Christ.

The goal of this article was simply to answer the question of who the Fathers of the Church were, why they are important, and how to begin exploring their writings.

Though I, like many, can’t help but roll my eyes over the uproar created by “The Da Vinci Code” many years back, we are indebted to Dan Brown in a way.

He reminded us that the early Church is terribly important. On its authority and fidelity hang the very reliability of the Scriptures and the Creeds shared by all Christians — Protestant, Catholic and Orthodox.

Of course, the events of “The Da Vinci Code” concerning what went on in the early Church is total fabrication. So where do we go for the truth? Simple. We need direct contact with the primary sources — that is, documents written by those who were actually involved in the events in question. Fortunately, abundant documents survive from the first eight centuries of the Church. We refer to those who wrote them as the early Church Fathers. By the way, contrary to the allegations of the characters in “The Da Vinci Code,” the documents we have from this era are not falsified or interpolated. Scholarly tools have existed for centuries that are particularly effective at detecting forgeries and dating documents to within a few decades of when they were written.

The good news is that there are thousands of documents and hundreds of writers. The bad news is that there are thousands of documents and hundreds of writers. Few of us have time to read them all. In fact, it is difficult to know where to begin.

The Church has put together a collection of short selections from the Fathers in the Office of Readings. These are the best introduction. The next step would be to read the Apostolic Fathers, the earliest of the post New Testament writings which have particular apologetic value given their proximity to the apostles.

Scripture, Liturgy, Biography

The Apostolic Fathers (ca. A.D. 95-150) were a lot like the apostles — simple men, without much formal schooling. That makes their writings easy to understand. But once we hit the middle to late second century, we run into very different kinds of writers. Justin had been a philosopher before his conversion, while Tertullian was a lawyer. Both were deeply cultured men, and concepts from the philosophy of their day, Stoicism and Platonism, surface frequently in their work. The same is true with Fathers from the fourth-to-fifth-century Golden Age, such as St. Augustine and St. Gregory of Nyssa.

So, is there any hope that the ordinary Joe or Jane can read these authors and make heads or tails of them?

Absolutely. And here’s why. Many of the most high-powered thinkers among the Fathers were also pastors. And many of their writings were originally addressed to the faithful as homilies, catechetical orations and lives of the saints. Though such writings are chock-full of insight and inspiration, they are delivered in words intended to be understood by everybody.

So my advice to those wishing to sink their teeth into the rich fare provided by these later Fathers is to focus on their exegetical and catechetical writings rather than the more philosophical treatises written for a more learned audience. What follows are a few concrete suggestions.

St. Basil and the Holy Spirit

Following the Council of Nicaea, there was a great deal of doctrinal confusion. One group of churchmen in the east said that while they accepted Nicaea’s definition of the divinity of Christ, they would not go beyond it to affirm the same of the Holy Spirit. After all, they pointed out, Jesus is called “God” (the New Testament Greek word is Theos) several times in the New Testament.

But the Scriptures never explicitly use the term “God” referring to the Holy Spirit. These “sola scriptura” bishops, called “pneumatomachoi” (fighters against the Spirit), therefore resisted the doctrine of the Trinity, one God in three distinct but equal persons.

St. Basil the Great responded to these heretics in the form of a short treatise that relies not on difficult philosophical concepts but on a common-sense examination of Scripture and the liturgy.

He demonstrated that Scripture constantly teaches the distinct personhood and full divinity of the Holy Spirit, but that it does so implicitly, as it does not explicitly call the Spirit “God.”

He then made one of the clearest cases against sola scriptura in early Christian literature, showing that Christians had never, from the time of the apostles to his day (ca. 370), relied exclusively on the text of the Bible to tell them how to pray and what to believe. He pointed to many liturgical traditions, such as the sacrament of chrismation (known in the West as confirmation), which had always been celebrated in the Church but were not clearly and explicitly spelled out in Scripture.

He also pointed to the fact that the Church had always, as far as anyone could remember, prayed the Trinitarian doxology — “Glory be to the Father, and to the Son, and to the Holy Spirit” — which clearly assumes the divinity of the Holy Spirit.

Lex orandi, lex credendi (the law of prayer demonstrates the law of belief) is a principle first clearly argued by St. Basil.

Therefore, to deepen your understanding of the work and person of the Holy Spirit, provide insight into the relation between Scripture and Tradition, and acquaint you with one of the greatest Fathers of the Eastern Church, pick up “On the Holy Spirit,” a short book by St. Basil, available in paperback from St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press.

Two Great Lives

In defending the divinity of Christ during the Arian crisis of the fourth century, St. Athanasius of Alexandria had received constant support from the most famous hermit of the Egyptian desert, St. Antony. Personally inspired by Antony’s story and example, Athanasius decided the world needed to know about him.

Without the internet, or even the printing press, Athanasius’ “Life of Antony” quickly became the rage throughout the Christian empire, which was copied, translated and passed from hand to hand.

It inspired many, including Augustine, to a deeper conversion to the Gospel and even to embrace religious life.

Antony, a hermit, was the “godfather” of religious life in the East. A few centuries later, St. Benedict established a communal form of life that made him the godfather of monastic life in the West.

Only a couple of generations after St. Benedict’s death, one of his monks was elected as successor of St. Peter.

Known as Gregory the Great, this monk-become-pope found time to write his “Dialogues,” the second book of which is a life of St. Benedict.

I vote that you put Athanasius’ “Life of Antony” and book two of St. Gregory’s “Dialogues” at the top of your reading list as a great way to get acquainted with two of the greatest monastic saints and two of the greatest Fathers of the Church.

Dr. Marcellino D’Ambrosio writes from Texas.

The Great Augustine

jorisvo/

Shutterstock.com

This presentation of the Fathers would not be complete without a discussion of how to break into the writings of the most famous Father of the Western Church, the great St. Augustine. Many praise Augustine, but virtually no one has read all of his works (he wrote more than 4 million words!). It’s hard to know where to enter the forest of his vast literary output. His “Confessions” is a classic of Western civilization as is his massive tome “The City of God.” But keep in mind that “Confessions” is not an autobiography in the typical modern sense of the word. It is a spiritual reflection on his past life, written soon after his accession to the episcopate, but it takes the form of a long, extended prayer to God. And its last few chapters ascend into the philosophical stratosphere, losing all but the heartiest astronauts. Is it to be attempted? Yes, but it is not really a beginner’s slope. And “The City of God” is definitely not the first Augustinian peak to be attempted either.

So, where to begin? In my opinion, it is his homilies and commentaries that are perfect for everyone — meaty enough for the most experienced, but simple enough for the novice. After all, his sermons are for ordinary people and are intended to help them understand and apply the Scriptures to their lives. Who cannot use a bit more of that? His commentary on the Psalms is fabulous. And, since his favorite topic is love, I especially recommend his homilies on the First Letter of John. Given that Augustine is the most influential teacher of the faith in the Western Church before St. Thomas Aquinas, he cannot be neglected by anyone wishing to tap into the Church’s ancient heritage.

Fathers of the Church

Greek Fathers

St. Anastasius Sinaita (d. 700)

St. Andrew of Crete (d. 740)

Aphraates (fourth century)

St. Archelaus (d. 282)

St. Athanasius (d. 373)

Athenagoras (second century)

St. Basil the Great (d. 379)

St. Caesarius of Nazianzus (d. 369)

St. Clement of Alexandria (d. 215)

St. Clement I of Rome, Pope (r. 88-97)

St. Cyril of Alexandria (d. 444)

St. Cyril of Jerusalem (d. 386)

Didymus the Blind (d. c. 398)

Diodore of Tarsus (d. 392)

St. Dionysius the Great (d. c. 264)

St. Epiphanius (d. 403)

Eusebius of Caesarea (d. 340)

St. Eustathius of Antioch (fourth century)

St. Firmillian (d. 268)

Gennadius I of Constantinople (fifth century)

St. Germanus (d. 732)

St. Gregory of Nazianzus (d. 390)

St. Gregory of Nyssa (d. 395)

St. Gregory Thaumaturgus (d. 268)

Hermas (second century)

St. Hippolytus (d. 236)

St. Ignatius of Antioch (d. 107)

St. Isidore of Pelusium (d. c. 450)

St. John Chrysostom (d. 407)

St. John Climacus (d. 649)

St. John Damascene (d. 749), last Father of the East

St. Julius I, Pope (r. 337-352)

St. Justin Martyr (d. 165)

St. Leontius of Byzantium (sixth century)

St. Macarius (d. c. 390)

St. Maximus the Confessor (d. 662)

St. Melito (d. c. 180)

St. Methodius of Olympus (d. 311)

St. Nilus the Elder (d. c. 430)

Origen (d. 254)

St. Polycarp (d. c. 155)

St. Proclus (d. c. 446)

Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite (sixth century)

St. Serapion (d. c. 370)

St. Sophronius (d. 638)

Tatian (second century)

Theodore of Mopsuestia (d. 428)

Theodoret of Cyrrhus (d. c. 458)

St. Theophilus of Antioch (second century)

Latin Fathers

St. Ambrose of Milan (d. 397)

Arnobius (d. 330)

St. Augustine of Hippo (d. 430)

St. Benedict of Nursia (d. c. 550)

St. Caesarius of Arles (d. 542)

St. John Cassian (d. 435)

St. Celestine I, Pope (r. 422-432)

St. Cornelius, Pope (r. 251-253)

St. Cyprian of Carthage (d. 258)

St. Damasus I, Pope (r. 366-384)

St. Dionysius, Pope (r. 259-268)

St. Ennodius (d. 521)

St. Eucherius of Lyons (d. c. 450)

St. Fulgentius (d. 533)

St. Gregory of Elvira (d. c. 392)

St. Gregory the Great, Pope (r. 590-604)

St. Hilary of Poitiers (d. 367)

St. Innocent I, Pope (r. 401-417)

St. Irenaeus of Lyons (d. c. 202)

St. Isidore of Seville (d. 636), last Father of the West

St. Jerome (d. 420)

Lactantius (d. 323)

St. Leo the Great, Pope (r. 440-461)

Marius Mercator (d. 451)

Marius Victorinus (fourth century)

Minucius Felix (second century)

Novatian (d. c. 257)

St. Optatus (fourth century)

St. Pacian (d. c. 390)

St. Pamphilus (d. 309)

St. Paulinus of Nola (d. 431)

St. Peter Chrysologus (d. 450)

St. Phoebadius of Agen (fourth century)

Rufinus of Aquileia (d. 410)

Salvian (fifth century)

St. Siricius, Pope (r. 384-399)

Tertullian (d. c. 222)

St. Vincent of Lérins (d. c. 450)