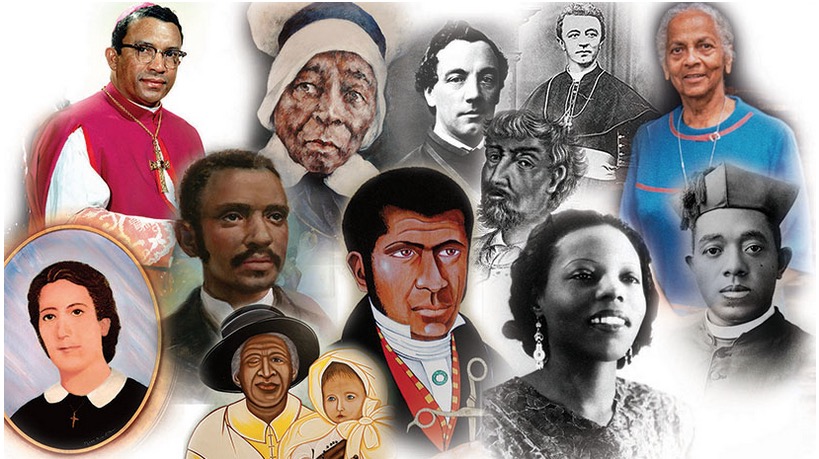

February’s celebration of Black History Month in the United States traces its roots back to the 1920s, but it attained more formal recognition in the 1970s, as is obvious with President Gerald R. Ford’s 1976 Bicentennial Year message about its importance. Ford described Black History Month as an occasion to “seize the opportunity to honor the too-often neglected accomplishments of black Americans in every area of endeavor throughout our history.”

Despite the many accomplishments of Black History Month’s goals, its often secular narrative forgets the contributions of Black Catholics. In recognition of that, the National Black Catholic Clergy Caucus of the United States began observing November as national Black Catholic History Month nearly 30 years ago. Nonetheless, in order to promote awareness of the accomplishments of all black Americans, it is important to promote an awareness of some of the many Catholic individuals who have achieved greatness in the face of racism’s plight — and in many cases the supreme greatness of holiness. No national celebration of Black History Month would be complete without including these Catholic stories — or the countless stories of black Catholics left untold.

Michael R. Heinlein is editor of Simply Catholic. Email him at mheinlein@osv.com. Follow him on Twitter @HeinleinMichael.

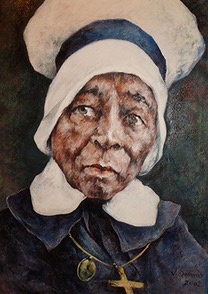

Venerable Mary Lange

Pioneer founded first U.S. order for black sisters

Not much is known about the first half of Mother Mary Lange’s life.

CNS photo

Born in Cuba, but possibly of Haitian background, Elizabeth Lange came to the United States shortly after the War of 1812, eventually making her way to Baltimore, where she settled. There, she ran a free school for African American children from her home. Sulpician Father James Joubert’s parish, in the same section of Baltimore, served a community of Black Catholics, many of whom were immigrants from the Carribean. In catechizing the children, he noticed that many of them were unable to read or write — particularly girls. Recognizing this, he saw a need for a girls’ school and asked Lange and collaborators to run it. Moreover, he encouraged her to establish the Oblate Sisters of Providence — the first successful establishment of black sisters in the United States. She had to tackle a variety of hurdles to achieve this work, as Baltimore’s Archbishop William E. Lori recognized: “She had many, many obstacles — among them racial prejudice and hatred — and her love overcame that in her life.”

The Oblate Sisters of Providence broadened their mission from its origins in schools under the leadership of Mother Mary Lange, eventually serving in a variety of educational and social capacities, including helping young women develop careers and operating homes for widows and orphans. Lange died in Baltimore on Feb. 3, 1882. The formal investigation into her holy life was opened in 1991 by then-Archbishop (later Cardinal) William H. Keeler of Baltimore. Lange was declared venerable in 2023.

Venerable Augustus Tolton

Canonization moves forward for country’s first black priest

Father Augustus Tolton knew what it meant to be abandoned and unwanted. Born the son of slaves, Tolton went on to be ordained the first African-American priest from the United States. But the path was not easy. He had to overcome many obstacles, including rejection from seminaries because of his race.

CNS photo

His family made a harrowing escape into Northern territory, settling in Quincy, Illinois. Father Peter McGirr, pastor of St. Peter’s Church in that city, took the young Augustus under his wing, granting him entrance to his parish school against the wishes of many in the parish. As a student at Qunicy College, Franciscan priests assisted Tolton as he sought the priesthood despite finding many doors closed in his face.

With heroic determination to fulfill the will of God, Tolton pressed on toward ordination despite the fact that no American seminary would accept him. Eventually ordained in 1886, after attending the Pontifical Urban College in Rome, Tolton expected to serve as a missionary to the African continent. However, he was assigned back to the United States — the Roman cardinal who ordained him noted, “America has been called the most enlightened nation; we will see if it deserves that honor. If America has never seen a black priest, it has to see one now.”

Father Tolton’s arrival in his hometown — about 20 years after the end of the Civil War — was met with racial prejudice by laity and clergy alike. The bishop’s delegate even told him white people should not attend his parish. Father Tolton persevered in humility and obedience and was eventually granted the opportunity to minister in Chicago by Archbishop Patrick A. Feehan in 1889.

In the Windy City, Father Tolton provided priestly care to a growing black Catholic community, which formed into St. Monica Church. He poured out his life in service to his people — in care for the poor and in a church building project, among other things. This strenuous work undoubtedly was a contributing factor to his death at the age of 43. After returning to Chicago by train from a retreat, Father Tolton collapsed in the street on a hot summer day and died on July 9, 1897.

Tolton’s canonization has been progressing since it was inaugurated in 2010 by Cardinal Francis E. George, OMI, of Chicago. Auxiliary Bishop Joseph Perry of Chicago — vice postulator of Tolton’s canonization cause — defines his legacy:

“His was a fundamental and pervasive struggle to be recognized, welcomed and accepted. He rises wonderfully as a Christ-figure, never uttering a harsh word about anyone or anything while being thrown one disappointment after another. He persevered among us when there was no logical reason to do so.”

Another step forward toward Tolton’s canonization was taken in December, when his remains were exhumed at his grave in his adopted hometown of Quincy, Illinois.

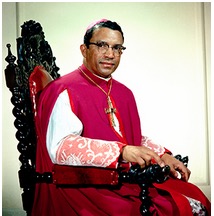

Bishop Harold Perry

First recognized black bishop in the U.S.

Photo courtesy of the Archdiocese of New Orleans

In the midst of the racial tumult of the 1960s, Bishop Harold Perry was named an auxiliary bishop in New Orleans in 1965, the same year as the Selma to Montgomery march. He was the first black bishop in the United States to be recognized as such; technically, the first was the biracial Bishop James Healy, who identified mostly with his father’s Irish heritage.

Ordained a priest for the Divine Word Missionaries in 1944, Bishop Perry became the 26th black priest ordained in the United States. After several years of pastoral work throughout the South, he became rector of the seminary operated by his order — originally founded to prepare African-American men for the priesthood.

Then-Archbishop (later Cardinal) Egidio Vagnozzi, apostolic delegate to the United States, is quoted as saying at Bishop Perry’s ordination, “the consecration of Bishop Perry was not an honor bestowed upon the Negro race, so much as it was a contribution of the Negro people to the Catholic Church.”

Bishop Perry was ordained at New Orleans’ St. Louis Cathedral in 1966 amid racist demonstrations outside, including a woman who characterized the event as “another reason why God will destroy the Vatican.”

New Orleans Archbishop Francis B. Schulte said of Bishop Perry at the time of his 1991 death, “he was a symbol of the great changes which have taken place in our Church and in our country.” Since Bishop Perry’s time, 23 African-American priests have followed in his footsteps and have been ordained bishops in the United States — including another of the same name: Chicago Auxiliary Bishop Joseph Perry (no relation).

Jean Baptiste Point du Sable

Chicago’s first settler

Photo courtesy of Chicago History Museum

Having lived in what would become America’s “Second City” during the 18th century’s last decade, Jean Baptiste Point du Sable is regarded as Chicago’s first settler. Not much is known about him before that, though historians claim the fur trader once had been arrested by the British on the Indiana frontier for charges of colonial sympathies.

It is said that the free du Sable survived the threat of enslavement, having lost his identification papers, by taking refuge in a Jesuit mission once he arrived in America. Believed to be from Haiti, it’s believed that he came to America by way of France, where he had attended school. While these details lack much documentation, surviving documents prove that du Sable married his wife of Potawatomi descent in the presence of a Catholic priest, and his funeral was held in a Catholic church in suburban St. Louis in 1818.

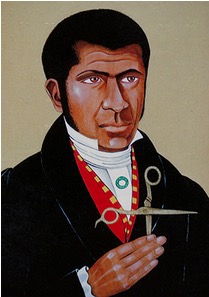

Venerable Pierre Toussaint

Ex-slave prospered, gave back in New York

CNS photo

In 1990, Cardinal John J. O’Connor of New York moved the remains of a black Catholic layman to a niche in the Bishop’s Crypt at St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York City. It was a stark contrast from the days when his race prohibited him from entering Old St. Patrick’s Cathedral in the city. Venerable Pierre Toussaint was the first and, to date, only layman to receive such an honor; the move was meant to foster devotion to his life and witness to the Gospel. Toussaint left a legacy of selflessness and charity.

Pierre Toussaint was born into slavery in modern-day Haiti and received his freedom in 1807. After arriving in New York City, he became successful as a hairdresser — earning a sizable salary, he saved his income to purchase his sister’s freedom as well as that of his future wife, Juliette. The couple offered their lives to God in care of the poor and needy. Together they adopted Pierre’s niece and provided for her education. They fostered and housed several orphans in their home over the years, and they were dedicated to doing works of charity throughout the city.

The Toussaints also offered much assistance to help their wards learn trades, in addition to operating a credit bureau and providing a shelter for immigrant priests. Pierre boldly crossed barricades to nurse the sick and destitute during a cholera outbreak. When urged to retire and enjoy his remaining years, Toussaint is quoted as saying, “I have enough for myself, but if I stop working, I have not enough for others.” He attended daily Mass for more than 60 years until he died in 1853, two years after his wife.

Lena Edwards

Doctor advocated against abortion, sterilization

Flickr.com

Flickr.comDr. Lena Edwards was born into a devout Catholic family in Washington, D.C., in 1900. The mother of six children, Edwards pursued a medical career as a means to help people.

The Catholic obstetrician was vocal in her opposition to abortion and sterilization and advocated natural childbirth. In her day, she worked among the poor and immigrants and taught at the Howard University Medical School. A consummate and successful professional, Edwards was awarded the highest American civilian honor in 1964 by President Lyndon B. Johnson — the Presidential Medal of Freedom. A devout Catholic all her life, Edwards was a daily Mass attendee. Born on the feast of St. Francis of Assisi, Edwards was very much devoted to him and the virtue of poverty. She was a professed secular Franciscan and was awarded the Poverello Award in 1967, given to those who exemplify the ideals of the Franciscan founder. She died in 1986.

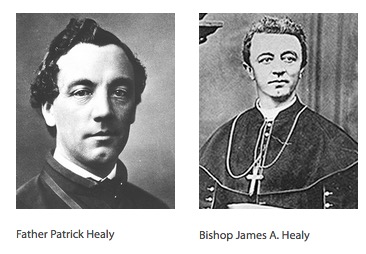

The Healy Family

A family of firsts in the U.S. Church

In the 19th century, a family of black Catholics attained many “first” accomplishments in the Church in the United States, although most people didn’t know they were black. That’s because the nine Healy children were born of a common-law marriage between a biracial slave and an Irish immigrant plantation owner in Georgia. Of them, three became priests — all of whom were trained in Paris, but controversially did not widely identify as black in their lifetime.

One became the first black president of a Catholic university in the United States — Jesuit priest Father Patrick Healy of Georgetown University. Father Alexander (Sherwood) Healy was a canonist who died at 39 in Boston. The oldest son became the first American bishop of African-American descent — Bishop James Augustine Healy, second bishop of Portland, Maine. Three daughters became nuns with the Congregation of Notre Dame — the order founded by St. Marguerite Bourgeoys in Montreal, Quebec. Sister Eliza Healy, CND, became the first superior of African-American descent in a religious community in the United States.

Daniel Rudd

Pushing for equality after the Civil War

Photo courtesy pf St. Mary’s Press

Daniel Rudd was a black Catholic layman who sought to bring about racial equality in Catholic parishes throughout post-Civil War America.

Born into a Catholic family — his father was a former slave — Rudd founded a weekly newspaper in 1886 for black Catholics in America as a means to harmonize racial divisions in the Church. His aims were to make the Catholic Church known to a wider audience of African-Americans, but also to break through the racism of his day. With his pioneering work, Rudd challenged the conscience of a nation and his Church. Eventually his work achieved the establishment of the first National Black Congress in 1889 — at which Father Augustus Tolton was the main speaker.

Julia Greeley

Former slave dedicated life to Denver’s poor

CNS photo

Born into slavery in Hannibal, Missouri, Julia Greeley first went to Colorado with the family of the first territorial governor, William Gilpin. She gained her freedom after the 1863 Emancipation Proclamation. As a slave, a beating resulted in a drooping eye.

While in Colorado, Greeley fell in love with the Catholic faith. Converting in 1880, she immediately immersed herself in the devotional and sacramental life of the Church; she attended daily Mass and took up intense fasting, along with constant prayer.

Greeley found great joy in her love for the Sacred Heart of Jesus, which she saw as the font for her many charitable and service-oriented ministries. She was known to spread the devotion, even using it as a tool to evangelize Denver’s firemen. The love she had for Jesus’ heart was expressed in her own merciful love for all she encountered.

Greeley took on a life of poverty, living in union with the poor of Denver. Taking on odd jobs like cooking and cleaning, she used her meager salary to finance a ministry to the poor.

In her trademark floppy hat, the holy woman dragged a red wagon filled with goods to distribute to her city’s poor. At times, she even took to begging for them.

A witness of God’s love and mercy to all, Greeley’s life shows the dignity of every life — especially those on the peripheries. Many of those whose lives she touched were among the nearly 1,000 mourners at her funeral in 1918. The canonization cause of Greeley was opened in 2016.

Venerable Henriette Delille

Order’s founder lived with generosity, love of God

CNS photo

The illegitimate daughter of a Frenchman and a free woman of color, Henriette Delille spent all her life in and around New Orleans’ French Quarter. Advancing into the status of high society as a young woman, Delille was schooled in French literature and instilled with a fondness for culture. Delille’s mother wanted her to take her place in the colonial plaçage system, where Delille hopefully would enter into a common-law marriage with an eligible man of European estate. In those days, women of mixed race weren’t able to fully espouse white men. It seems as though Delille rejected the idea, since no record exists. However, some parish records show the possibility of her having birthed two sons who died in infancy, although it is uncertain if that’s the case. It’s clear, though, that, after receiving the Sacrament of Confirmation, Delille was a changed woman. She lived by the following, written in her prayer book: “I believe in God. I hope in God. I love. I want to live and die for God.”

In her teenage years, she became influenced by the religious sisters with whom she taught alongside since she was 14. Though she believed she was called to religious life, two communities denied her entrance because of the color of her skin.

Not deterred by rejection, though, Delille’s resilience brought her to establish a religious congregation herself in 1836. With the funds inherited at the time of her mother’s death, Delille began what became known as the Sisters of the Holy Family. The order’s original mission was to serve the poor and sick and provide religious education to both slaves and free persons. Her generosity and love was known to everyone who knew her. Sacramental records show Delille served as the godmother and marriage witness of many.

Delille died at the age of 49 on Nov. 16, 1862, having spent her young life in love and service of others.

Delille’s cause of canonization opened in 1988, and she was declared Venerable in 2010.

Mary Lou Williams

Musician finds faith in Christ’s Church

Photo courtesy of Duke University

Life as a globetrotting musician caught up with Mary Lou Williams while performing at a Paris nightclub in 1954. The jazz pianist and composer later said that the “‘greed, selfishness and envy” she saw in her life caused her to get up and walk out that night mid-performance and leave her career. “I got a sign that everybody should pray every day … I had never felt a conscious desire to get close to God. But it seemed that night that it all came to a head. I couldn’t take it any longer. So I just left — the piano, the money, all of it,” she said.

She spent the next three years in something of a contemplative state, passing the majority of her days in prayer at a Catholic church near her New York City apartment, which she loved because it was the only church she could find open at all hours.

After converting to Catholicism in 1957, Williams was a changed woman.

Williams returned to music at the urging of many friends, including priests and jazz legend Dizzy Gillespie. Her revived career reflected her new-found faith and included a mix of teaching and composing — including three Mass settings and a well-known piece honoring St. Martin de Porres.

“I am praying through my fingers when I play,” she said. “I get that good ‘soul sound,’ and I try to touch people’s spirits.” Williams died in 1981.